First Person: Mark Brown looks back 15 years to the immediate aftermath of the Canterbury Earthquakes

15 September 2025

Written by Mark Brown

In the first article of a series, landscape architect Mark Brown recalls living and working through the Canterbury Earthquakes and the early days of the City’s recovery.

I’m in my office on Cambridge Terrace, looking across the Ōtākaro Avon River towards the new Te Pae Christchurch Convention Centre, the wonderfully restored Midland Building, the protected shell of the Gothic Revival-style Canterbury Provincial Council Buildings, and the bones of Noah’s Hotel which will reemerge as the Sheraton Christchurch in 2027. In the same line of sight, there is a gap where the building I worked in used to stand. Boffa Miskell’s Christchurch office occupied floors 6 and 7 of the Brannigans Building (previously The Cardinal Network Building), which was widely recognizable from the two glass elevators at the front corner of the building next to Oxford Terrace.

It’s nearly 15 years since Cantabrians were shocked awake in the early morning of September 4, 2010; and then experienced far greater tragedy on February 22, 2011. Taking in the view is a time to pause and reflect on the lives lost and changed forever, and the transformed cityscape.

I’ve been remembering what it was like to live and work through the immediate aftermath and the initial recovery phase. The real uncertainty around what was going to happen to my family and property. My daughter was 2½ and my son was 7 months old - would our house be repaired and when would that happen? Work was even more precarious. All but one of the projects I was working on had stopped in an instant and there was no longer an office to go to.

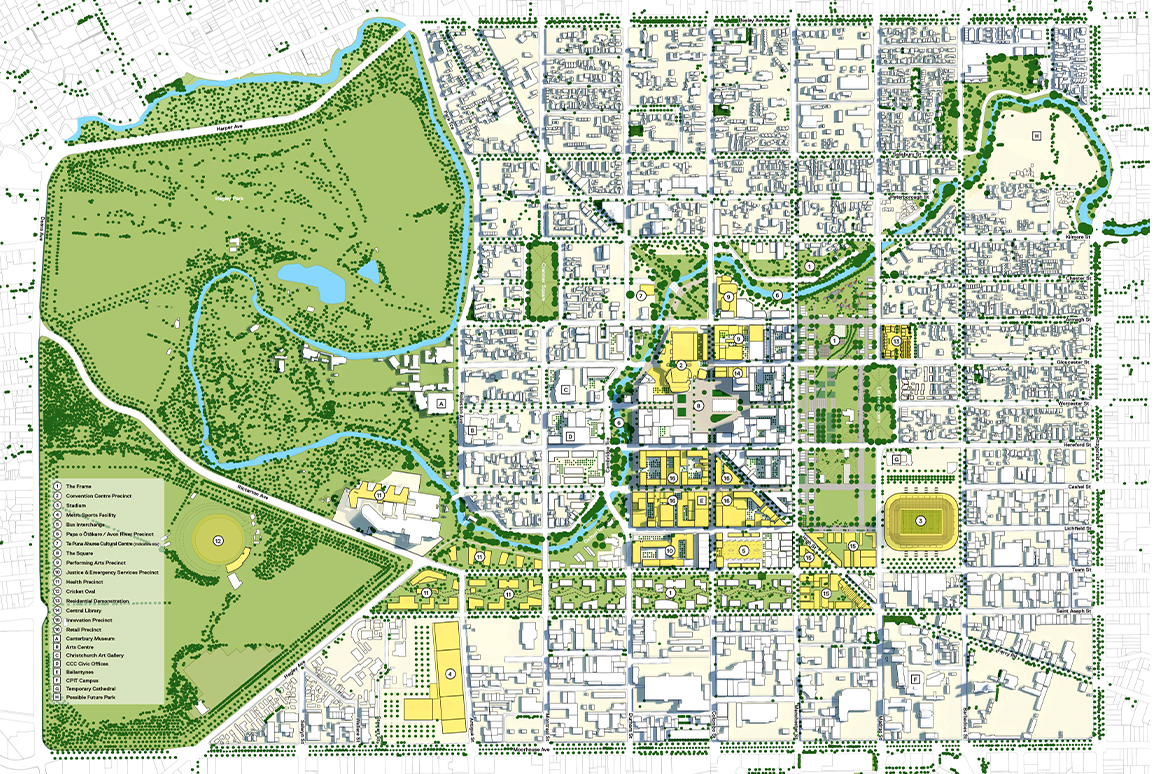

While we adapted and coped with Christchurch’s ‘new normal’, two key recovery decisions made by the government would significantly impact my personal and professional life and go a long way to shaping the future of Christchurch. The Central Christchurch Recovery Plan – perhaps better known as The Blueprint– and the Red-Zoning of residential properties in east Christchurch, Kaiapoi, Brooklands, as well as Kairaki and Pines Beach, provided a starting point for both long- term recovery and for people to move on with their lives.

At first, for me, the greatest impact of the September 4 earthquake was a big fright. With no damage to my house in Burwood, and after a couple of days off work until our offices were checked as being safe to occupy, there was an uneasy return to normal life. Like most of my colleagues at Boffa Miskell, I was back in the office within a week – sometimes work was disrupted by aftershocks, but projects continued, and we got used to what we thought was our post-quake existence.

My house was close to the Ōtākaro Avon River, so I didn’t have to venture far to see what had happened to those less fortunate. Lateral land spread and subsidence had damaged many houses along the river corridor. I also learned about liquefaction, as friends in Avondale had piles of silt bubbling up in their front yard. Then February 22 changed everything. I was fortunate to be at Christchurch Airport for a meeting and site visit when the earthquake struck. I’d taken a company vehicle, so I had a way to get home and didn’t endure the horrific experience of being in the office at the time. Many of my workmates were, and their later recounting of what happened in the City Centre sounded terrifying.

Making contact with my family quite quickly and knowing that they were safe was a huge relief. But as I made my way from west to east Christchurch, the scale of damage increased and the severity of what had happened became increasingly apparent. A trip that normally took 15 minutes lasted nearly three hours and the closer I got to home, the worse things were: increasing amounts of silt from liquefaction turned into flooding, which then turned into giant cracks and fissures in the road surface. I turned into my street to see a small car being slowly pulled out of a sink hole. It had been completely submerged.

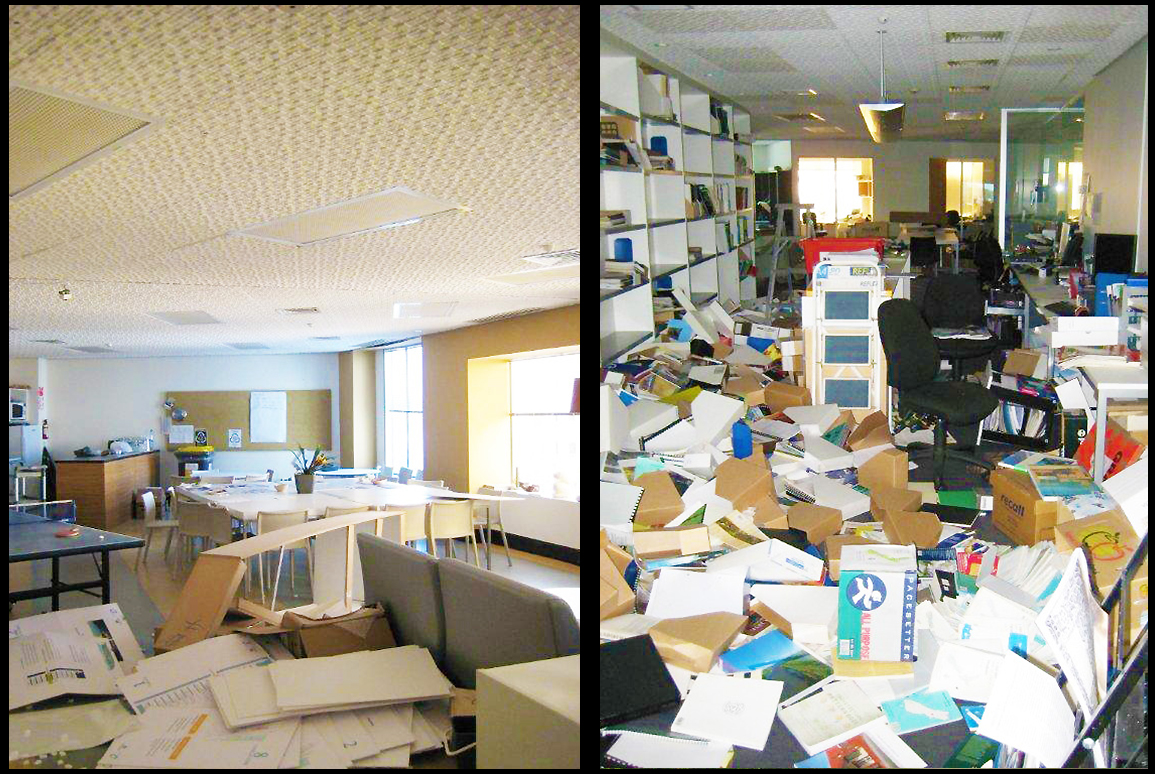

The house was chaos. Inside, it was like every room had been ransacked. Outside was not much better. It was a typical single storey 1960’s 100m² Summerhill Stone home and, as with many others like it in Christchurch, the cladding system hadn’t performed well.

We couldn’t stay. We gathered some clothes and made our way to my parent in Bryndwr, a relatively undamaged west Christchurch suburb, and then went to Motueka for a few weeks. After some temporary repairs, a big clean-up effort, and power and water reconnected, we returned home over a month later.

But what would happen next? The Red Zone announcement in June is prominent in my memory – some certainty was provided by notification of the residential areas that would be red-zoned, along with the technical land classifications for other areas that would direct how those houses would need to be prepared. That my house was in a Technical Category 2 (TC2) area was considerable relief. New words were added to the lexicon of post- earthquake Christchurch. Under cap? Over cap? TC2 or TC3? These terms and acronyms became the basis of many conversations.

We lived in a damaged house for over two years. It was a long time before the sewer was working (I’ll be happy never to use or empty a camp toilet again), and heavy snowfalls in July and August 2011 added to an already challenging situation. But there was comfort in having the certainty that the house would, eventually, be fixed.

Professionally, things were more ambiguous. As a landscape architect, my work was design and documentation, as well as overseeing project construction. Much of this was paused as planning for the recovery swung into action.

For the first few weeks, most of our equipment, computers and files were stuck in the office behind the restricted access of the central city cordon. Boffa Miskell’s management team quickly gained access to the office to recover critical equipment and files, organizing new laptops and taking steps to lease new office space near Christchurch Airport.

In the interim, we worked in small groups from homes that had wifi. Looking back, and comparing “WFH” in 2010 to the COVID lockdowns of 2020, it’s hard to imagine how we got much done without Teams or Zoom; or centralized servers and cloud-based file storage. In 2010 Boffa Miskell had a primitive system, Citrix, which we could use to access files held on our Auckland-based server, but you had to download the files to your desktop, work on them, and then upload them again, slowly, at the end of the day.

At the end of 2011 I became involved in initial work by the Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority (CERA) to consider how the Residential Red Zone land could be treated in an interim state, once houses were removed. This project evolved into something I would work on for the next four years, and provided an opportunity to help manage the land where housing was being cleared, while developing landscape outcomes that were respectful to those residents who were in neighbourhoods close to the Red Zone, staying, or in the process of moving on.

The announcement of The Blueprint in early 2012 was a significant step in the recovery process. My colleagues and I were very proud to be part of one of the local companies that contributed to the plan. It was a real milestone for landscape architects, architects, urban designers and planners in Aotearoa New Zealand to play critical roles in the project. We were intrigued to see the plan would look like – Don Miskell, Rachel de Lambert, Ken Gimblett and Marc Baily all worked remotely in the ‘100 Day Blueprint’ project office and the plan they were developing was closely guarded.

I asked Ken Gimblett, a senior planner and Boffa Miskell Partner, about his experience. He talks about the intensity, lack of sleep, fast pace and pressure that defined those 100 days for him; but what is perhaps more revealing is Ken’s reflection that the project was the professional opportunity of his career, but initially not one that could be trumpeted or celebrated due to the turmoil and challenges that many in Canterbury and beyond were still facing.

I can relate to this – there is certainly some unease in reflecting on career highlight projects that are a direct result of an event that caused loss of life and turmoil. For many of us in the design community, there were real highs and lows: sorrow and uncertainty from what was lost, were very much in contrast with the excitement and creative energy at the prospect of re-designing a city. I have certainly benefited professionally from being part of teams that delivered the award-winning Te Papa Ōtākaro Avon River Precinct, and the soon-to-be opened Parakiore Recreation and Sport Centre (Metro Sports Facility).

Later in our discussion I ask Ken which of the Anchor Projects identified as part of The Blueprint does he think is the most successful and why? His answer surprised me. While he acknowledges the impact and benefits of several of the completed Anchor Projects, he considers that The Blueprint itself is the most important. It provided ‘a plan’ when one was sorely needed, securing central government backing and providing confidence for recovery investment from both the public and private sectors. And, certainly for the design community in Canterbury, there was a feeling of assurance in knowing that there was a ‘brief’ that we could respond to.

Looking over the Ōtākaro Avon River is a great snapshot of the ongoing recovery of Christchurch’s central city. Despite some of the incredibly ambitious timeframes originally presented for the completion of anchor projects, The Blueprint was always a 30-year long-term plan. So we’re about halfway there and making good progress.

Within my view, two of the Anchor Projects – Te Pae Christchurch Convention Centre and Te Papa Ōtākaro Avon River Precinct – are high quality outcomes, representative of the foresight and investment that has revitalized the central city. I’m particularly proud of my work on The Avon River Precinct, it has vastly improved the public realm along the Ōtākaro Avon as it winds through the central city. Te Kaha Stadium and Parakiore Recreation and Sport Centre are near to opening, and these new facilities, along with some great private developments like the Riverside Market and The Crossing retail precinct, are adding to a building sense of optimism and pride in the city.

It is undeniable that parts of the City’s built form are unrecognizable compared to 15 years ago; but the same could be said for parts of Auckland or any city. Here, many quintessential ‘Christchurch’ buildings remain – the Town Hall, The Arts Centre, Ballantynes. With patience and funding, we hope to see the Christ Church Cathedral and Provincial Chambers returned to their former glory. These landmark buildings provide a sense of familiarity, as does the underlying fabric of the city. The grid arrangement of the central city is largely intact, and green spaces like Victoria Square, Latimer Square and the meandering Ōtākaro Avon River help ground those that might be temporarily disorientated.

What will the central city and the Ōtākaro Avon River corridor extending out through the city’s east look like in another 15 years? I think it’s going to be just fine.