A collaboration of Mātauranga Māori and Western Science in Tauranga Harbour

10 September 2025

Written by Tyla Kettle

Under the Te Paritaha Monitoring Programme, the humble pipi (Paphies australis) holds significance far beyond its ecological role.

For generations, pipi have been a vital source of kai and a key link between mana whenua and the moana. Like many taonga species, pipi face mounting pressures from environmental change, development, and shifting dynamics.

Recognising this, Tauranga Moana Iwi Customary Fisheries Trust (TMICFT) and the Port of Tauranga engaged Boffa Miskell to develop and implement a monitoring programme that weaves mātauranga Māori (traditional Māori knowledge) and Western science, resulting in the Te Paritaha Monitoring Programme, required as a condition of consent for port operations.

Te Paritaha (also known as Centre Bank) is a large shoal forming the main area of the flood tidal delta. Its shallow sandflats, which become exposed at low tide, have long provided a rich mahinga kai for the iwi of Tauranga moana, including Ngāti Pukenga, Ngāi Te Rangi, and Ngāti Ranginui, all of whom make up the TMICFT and are recognised as kaitiaki. Historically, the iwi and hapū of Tauranga moana consider Te Paritaha a common meeting place to help resolve conflict and politics amongst themselves whilst gathering kai.

Pipi are an ecologically important species in soft sediment ecosystems. They are filter feeders — helping improve water clarity and quality, as well as disturbing and reworking sediments through their burrowing and feeding. Their dual role culturally and ecologically makes them an important focus for the Te Paritaha Monitoring Programme.

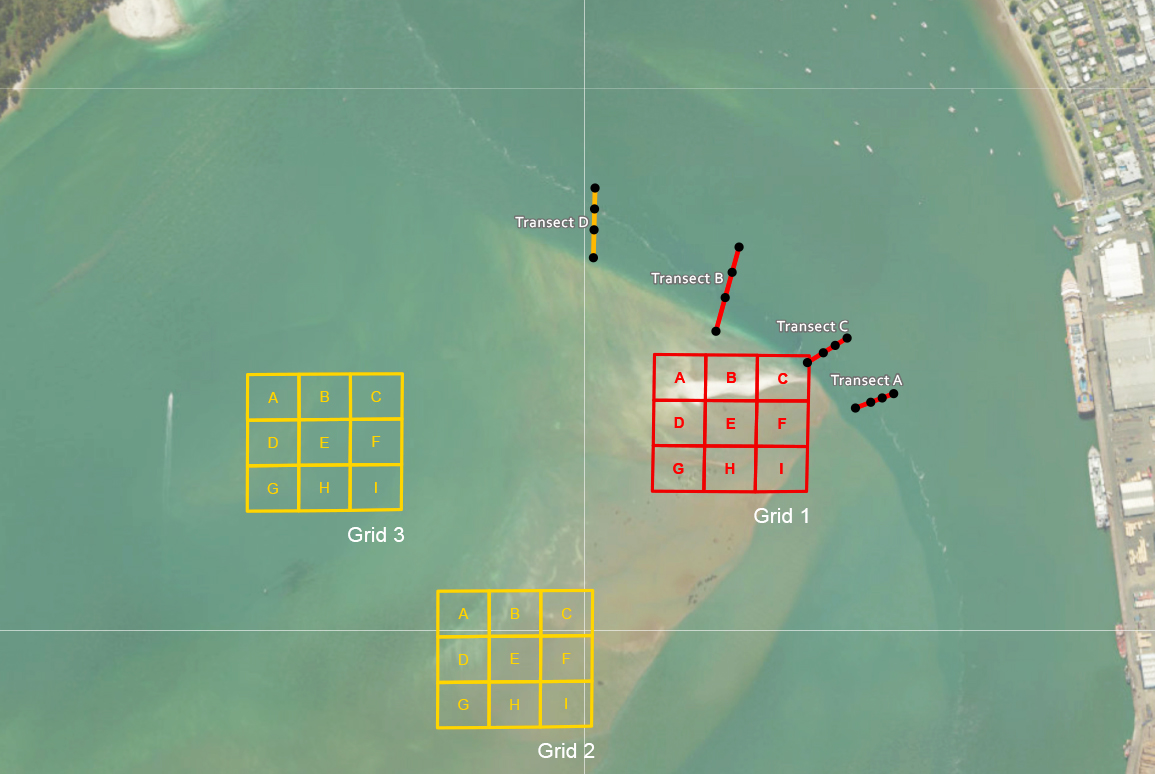

Tauranga Moana Iwi Customary Fisheries Trust helped shape the programme from the outset, identifying culturally significant sites for sampling locations. Surveys began in 2022 and combined grids, transects, sediment testing and pipi contaminant analysis. Each round of monitoring consists of 2-3 days of sampling, and the Boffa Miskell team reaches out to iwi and hapū so they have an opportunity to get involved. Our aim is to learn from each other and always look to adapt and better the monitoring programme.

Pipi abundance, size, and sediment grain size are measured. Pipi prefer medium-sized sands that don’t clog their gills whilst feeding. An iterative approach ensures both mātauranga Māori and western science inform each stage.

The programme has captured variability in pipi population dynamics across Te Paritaha, and patterns differ across survey sites. Intertidal areas are dominated by small juveniles, transition zones show fluctuating mixes of both juveniles and adults, while deeper subtidal areas retain more numerous adults.

Overall, most sediment and pipi flesh samples fall below the default guideline contaminant values. However, in March 2024 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) were detected, likely from a heavy oil spill which occurred in the harbour on the same day as sampling. Encouragingly, levels had decreased by May when resampling occurred. While pipi filter-feeding biology allows them to process contaminants quickly, the incident reinforced iwi concerns about the long-term sustainability of kaimoana.

Perhaps the most important outcome so far is the partnership itself. Each survey involves iwi and hapū volunteers, turning fieldwork into shared learning. TMICFT leadership has ensured the programme reflects both ecological and cultural outcomes, while scientists have adapted methods as new knowledge emerges.

TMICFT has called for more mātauranga Māori to be embedded into monitoring and interpretation ensuring that the dataset grows not just in size, but in cultural richness. Embracing more mātauranga Māori means integrating Māori knowledge systems, which are rooted in holistic, intergenerational, and environmentally focused wisdom, alongside western science (systematic approach to understand the natural world through observation, experimentation and evidence-based reasoning) to create more sustainable and culturally inclusive outcomes.

We hope to keep up biannual monitoring for a number of years so we can continue to share and receive knowledge. We see this as an opportunity to develop a large dataset on pipi size and abundance in Tauranga Harbour. Monitoring will capture seasonal changes and, hopefully, the next mass recruitment event (influx in juvenile pipi post spawning). Over time, our work will provide invaluable insights into pipi population dynamics, informing restoration and customary harvest management.

The Te Paritaha Monitoring Programme is more than data collection. It is a model for how Aotearoa can approach ecological monitoring where mātauranga Māori and Western science are woven together, communities are active participants, and taonga species are cared for with both rigour and respect.